Release Date:

Downloads include choice of MP3, WAV, or FLAC

Sweet Time, like the albums Open, to Love, Hands On, Tears, and Changing Hands, is an elliptical, mystifying masterpiece that displays Bley's uncanny knack for creating crystalline, gleaming musical structures from the most minimal of means. Take for instance a spontaneous balladic composition such as "Never Again," with its gently dissonant skeletal body that becomes a ghostly study in intervallic extension -- along a row of eight notes and a host of chords built from their rearrangement into a new architecture, equally spare but far from sparse. It's a piece that requires an emotional response to enter initially because so little is apparent to the ear. When, in the middle of the tune, he shifts into droning regal chords and staggering arpeggios that leap into the scalar heavens from the original chords and pitches, the effect is stunning, breathtaking.

On the tune "Contrary," Bley constructs two-handed melodic counterpoint. In the top middle register he flows scales and arpeggios together that stagger one another, while in the lower middle register he undoes them by taking the root note of the root chord and reflecting the second, not the current, arpeggio in the right hand. In the lower scale he moves through both Handel and Pachelbel for grins before striking it all and entering into a quick study of minor sevenths and diminished ninths.

On the title track, Bley reveals what makes him a legend in the history of jazz and not -- as the snot-nosed new breed of "cultural" critics would have him -- a footnote. Bley moves a standard ragtime meter and creates a rhythmic counterpoint by shifting into deeper blues waters. Here again, in the lower middle register of the piano, Bley finds the elemental means by which to construct a narrative that is at once elliptical yet rooted in traditions so old you can smell the dirt. Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, Bud Powell, and Roosevelt Sykes all make their voices heard in Bley's blues.

As if that wasn't enough, he shifts his focus briefly to a different kind of blues: Occidental and Oriental blues, as if trying to create a musical mythology in scalar phrases and open, droning, modal chords. There are places in Bley's music, especially when he digs in, playing an idea over and over again and altering it note by note until it suddenly emerges in an entirely new construct, that spoken -- or in this case written -- language ceases to have meaning because it cannot convey even a simile of what is transpiring in the music. That Bley's music is original is a given, that its beauty is towering is an understatement, that it can only be comprehended in the depths of the human heart is simply the truth.

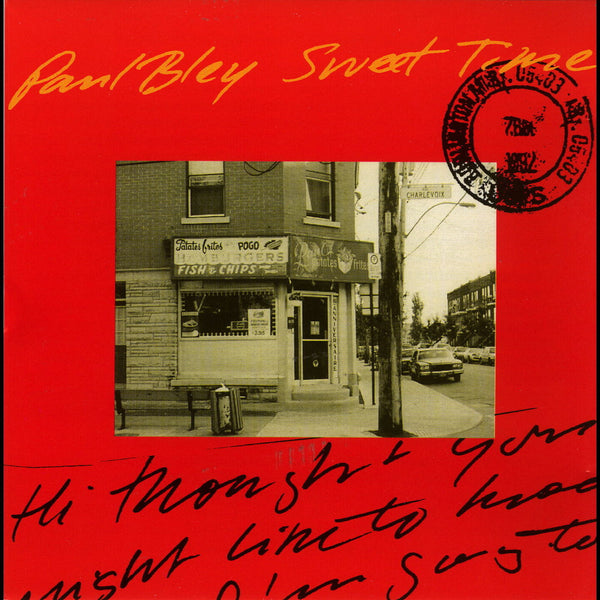

Sweet Time

Paul Bley

$9.99

Downloads include choice of MP3, WAV, or FLAC

Sweet Time, like the albums Open, to Love, Hands On, Tears, and Changing Hands, is an elliptical, mystifying masterpiece that displays Bley's uncanny knack for creating crystalline, gleaming musical structures from the most minimal of means. Take for instance a spontaneous balladic composition such as "Never Again," with its gently dissonant skeletal body that becomes a ghostly study in intervallic extension -- along a row of eight notes and a host of chords built from their rearrangement into a new architecture, equally spare but far from sparse. It's a piece that requires an emotional response to enter initially because so little is apparent to the ear. When, in the middle of the tune, he shifts into droning regal chords and staggering arpeggios that leap into the scalar heavens from the original chords and pitches, the effect is stunning, breathtaking.

On the tune "Contrary," Bley constructs two-handed melodic counterpoint. In the top middle register he flows scales and arpeggios together that stagger one another, while in the lower middle register he undoes them by taking the root note of the root chord and reflecting the second, not the current, arpeggio in the right hand. In the lower scale he moves through both Handel and Pachelbel for grins before striking it all and entering into a quick study of minor sevenths and diminished ninths.

On the title track, Bley reveals what makes him a legend in the history of jazz and not -- as the snot-nosed new breed of "cultural" critics would have him -- a footnote. Bley moves a standard ragtime meter and creates a rhythmic counterpoint by shifting into deeper blues waters. Here again, in the lower middle register of the piano, Bley finds the elemental means by which to construct a narrative that is at once elliptical yet rooted in traditions so old you can smell the dirt. Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, Bud Powell, and Roosevelt Sykes all make their voices heard in Bley's blues.

As if that wasn't enough, he shifts his focus briefly to a different kind of blues: Occidental and Oriental blues, as if trying to create a musical mythology in scalar phrases and open, droning, modal chords. There are places in Bley's music, especially when he digs in, playing an idea over and over again and altering it note by note until it suddenly emerges in an entirely new construct, that spoken -- or in this case written -- language ceases to have meaning because it cannot convey even a simile of what is transpiring in the music. That Bley's music is original is a given, that its beauty is towering is an understatement, that it can only be comprehended in the depths of the human heart is simply the truth.